From Lab to Tundra: Building a More Efficient Future with Rural Alaska

In a small Athabascan village on the Yukon River, a new house is going up. Two workers raise a truss onto an elevated foundation and another one nails it to the support beam. A mountain of insulation sits on the tundra, waiting to be filled in. Tribal leaders in Huslia, Alaska, hope these homes will attract health care and law enforcement workers to the remote Arctic community.

Those are the two positions they desperately need, said Mitch Shewfelt, who is overseeing construction of the new homes. With no roads in and out of Huslia, the nearest police are more than 100 miles away. “If there’s a threat in the village, there’s no one there to immediately take care of it.”

Hundreds of miles away in Mountain Village, near the mouth of the same river, a crew unloads a barge full of materials. It holds everything they need to build six super-insulated tiny homes, which will help alleviate overcrowding in the Yup’ik village and, more immediately, provide shelter for those most at risk from coronavirus.

It is construction season in Alaska, or, in local terms, the short window between duck-hunting season and moose-hunting season. The few months of the year when the ice vanishes, the tundra blooms, and the sun shines nearly around the clock. It is a precious time to load up on fish and berries and firewood for the long winter ahead.

Staying warm is the center of life at this latitude, and the driving purpose of the Cold Climate Housing Research Center (CCHRC), an Alaska-based lab that joined the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in June with a focus on the Arctic and extreme energy efficiency. For 20 years, the center has been developing building technologies in some of the world’s harshest conditions. But the research is not confined to its lab in Fairbanks. The real tests happen out here, on the tundra, where temperatures dive to minus 50 and energy costs soar to more than five times the national average.

“We learn from the lab. We rely heavily on the building scientists,” said Aaron Cooke, an architect at CCHRC-NREL. “But we never forget that buildings are for people.”

That means combining the latest technologies with a deep well of traditional knowledge. Alaskans have always been an innovative bunch. Since the First Alaskans set foot on this continent over 10,000 years ago, life has been an almost constant battle to survive, to scrape together enough food for winter, to build shelters that would keep them warm. When it comes to adaptation, they are experts in the field.

Today they are adapting to a new reality: a housing and energy crisis that spans much of the circumpolar north. In places like Huslia and Mountain Village, the housing stock is failing. Homes imported in the 1970s and ‘80s were not appropriate for the extreme climate or the frozen ground. Most are cold, leaky, and very expensive to heat. High levels of mold and rot have created widespread health problems for Alaska Native communities, who suffer from the highest rates of respiratory disease in the nation.

Mountain Village is no exception, said John Agwiak, with the Asa'carsarmiut Tribal Council. Many homes in the village have black mold and rotting floors, thanks to poor insulation and shoddy plumbing.

“Some floors are so caved in you can see outside to the ground,” he said.

CCHRC-NREL tackles these issues from the ground up—literally. With 80% of the land in Alaska underlain by ice-rich permafrost, there is no such thing as a stable building site. Examples can be found in almost any community–doors that will not close, walls pulling away from the floor, or—in the worst cases—homes sinking into the ground, losing a battle to the ever-changing earth. In southwest Alaska, where Mountain Village is located, the permafrost is changing faster than anywhere—thawing and sinking from the top down like an ice cream cake left in the sun. In the next two decades, almost all the permafrost is expected to thaw down to 1 meter, leaving a chaotic surface pocked with sinkholes, grassy tufts, and pools of water. Building on this kind of soil is difficult, especially on a limited budget.

To address this problem, CCHRC-NREL designed foundations for the new homes that can be easily adjusted by their occupants. The homes sit above the ground on threaded jacks bolted to steel beams. If the ground shifts over time, the homeowner simply manipulates the jacks to bring the home back to level.

Energy efficiency is another top priority. Alaska’s rural communities burn diesel for both heating and electricity. Even though it is heavily subsidized, they still pay the highest energy costs in the nation. In Mountain Village, diesel runs about $6.50 a gallon, Agwiak said, and some households spend up to half their income on energy.

In this context, efficiency comes first.

“We always start with the envelope,” Cooke said. “The northern animal doesn’t eat more in the winter to stay warm. They grow thicker fur or blubber.”

When it comes to buildings, that means packing on the insulation. The Mountain Village homes use a technique called REMOTE (Residential Exterior Membrane Outside insulation TEchnique). Adapted from Canadian building scientists, the REMOTE wall consists of a 2x4 frame wall filled with fiberglass batts, with an additional six inches of rigid foam attached to the outside. The idea is to move the majority of the insulation outside the structure to create a thick, airtight envelope with no thermal bridging—similar to wearing a heavy parka with no rips or seams. Using a vapor-impermeable insulation like rigid foam on the outside keeps condensation from forming in the wall—preventing the mold and rot problems that plague many Alaska homes.

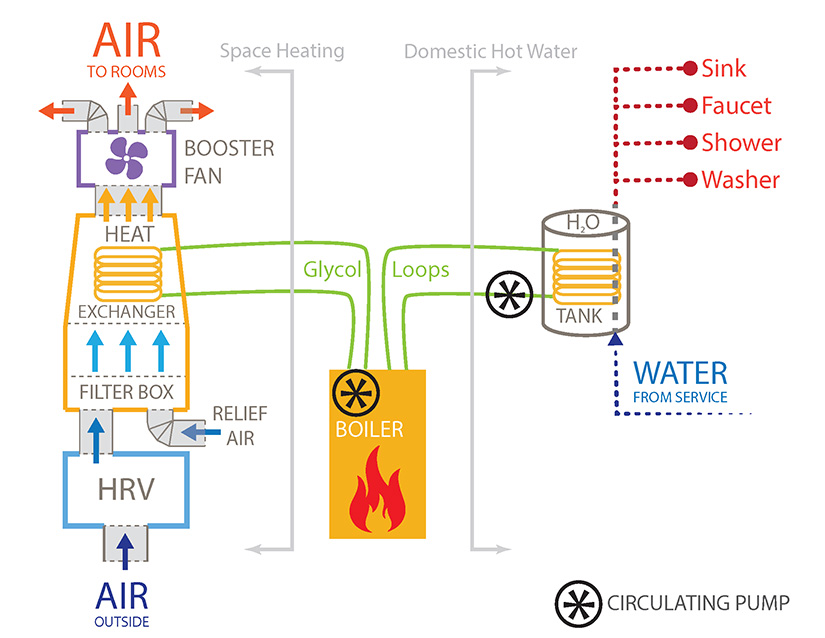

Of course, with such tight envelopes, ventilation is key to keeping families healthy. CCHRC developed the BrHEAThe System to ensure these airtight homes would receive enough fresh air. Through pairing a heat recovery ventilator with a high-efficiency boiler, BrHEAThe combines heating and ventilation into a single system, so that whenever the home is receiving heat it is also receiving fresh air.

Those are just a few ways CCHRC-NREL technology is trickling from the lab all the way to the Arctic tundra. But just as important as technology is culture. Like anywhere in the world, a home must reflect the lifestyle and identity of its occupants. Over the past century, however, this need was sorely overlooked in rural Alaska. A cornerstone of CCHRC-NREL’s work is to bring culture back into housing.

“When you come into a community, you have to be willing to start over and listen to what they need,” Cooke said. “What’s their desired amount of modernization, and what is the desired amount of traditional values that need to remain present?”

A prototype home in Anaktuvuk Pass is the perfect illustration. The village sits on a windy pass in the Brooks Range, with no trees or natural buffers from the Arctic weather. For generations, the Inupiaq people carved sod igloos into the hillside to stay warm. When CCHRC designed a home with the community in 2008, they blended traditional principles—such as living underground—with advanced technologies like a floating foundation and a thick polyurethane shell.

The earth-bermed shelter is a clear throwback to the sod igloos of the past. But sometimes the connection is not as obvious. The Mountain Village homes, for example, may just look like tiny boxes sitting on bright red car jacks and wood footings. But they are actually much more—a healthy refuge, a safety net for elders, a weapon against homelessness.

“They will make families very happy this winter,” Agwiak said. “Because they don’t have to choose between heating their home and eating, or buying food or paying for electricity, or paying for the cost to go to medical.”

In a few short weeks, ice will start running on the Yukon River, first forming delicate pans that float on the surface, then solidifying into a thick crust that can support snowmachines, dog teams, and herds of caribou. In places like Huslia and Mountain Village, the world gets quiet. Life slows down.

This winter, a few more people will be warm inside.

Learn more about the new NREL-CCHRC Partnership.

Last Updated May 28, 2025