Fuels Researcher Gina Fioroni Runs Past Lab—and Trail—Obstacles

When National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Senior Scientist Gina Fioroni was a young girl, she and some friends came up with a brilliant idea.

“Mom had a clothesline tied to a tree on an embankment,” she said with a smile. “That rope ran to the house. I thought we could make a really cool sky ride if we’d attach a bucket to the line and cruise down.” After climbing up several feet in the tree and preparing to launch, the future scientist learned at least one important lesson. “Guess what doesn’t hold the weight of a bucket and kid?” she laughed. Crashing was no big deal. “It wasn’t the first time I’d fallen out of tree.”

But such experiences formed a lasting philosophy: “Nothing ever goes the way you planned.” It informs her chemistry research with fuels and has enabled her to finish marathons in all 50 states as well as 100-mile and longer ultradistance runs. “Tenacity is a necessary character trait for being able to slog through 100- or 200-mile races. It’s not easy. I’ve wanted to quit, but my determination and passion for the sport keeps me going,” she said. “The same holds true for some of the projects I work on at the lab—they can be challenging, seem never-ending and full of setbacks—but I never give up,” Fioroni said. “I continue to develop solutions until I find one that solves the problem.”

There is another area where her interests overlap. “As a long-distance runner, I have a love and respect for the outdoors, and NREL is focused on improving the environment and sustaining it for generations to enjoy,” Fioroni said. “I love that I have a small part in that.”

The 10-year NREL employee has hit her stride and was recently promoted to NREL Senior Scientist in the Fuels and Combustion Sciences department. “Gina demonstrates natural leadership qualities and is a future leader for the group,” said NREL Research Fellow Bob McCormick, her mentor, adding “she has completed milestones and many other programmatic requirements while also running a large number of challenging experiments.“

Her pursuits outside the laboratory boost her professional career track. And even though it typically takes a few weeks to recover from some epic endurance contests, she rebounds and dives into research. In 2019, after she became the first American woman to complete the 144-mile Eufòria trail in Spain, Fioroni returned to NREL and, her first day back, took part in a photo session with her co-authors to promote a paper published in the journal Applied Energy titled "Impact of Ethanol Blending into Gasoline on Aromatic Compound Evaporation and Particle Emissions from a Gasoline Direct Injection Engine."

It was one of many high-impact publications featuring her research. McCormick cited Fioroni’s contributions as the lead author on three of five major journal articles she published in 2019. She is also much sought after for collaborations across NREL centers, as well as for her insight in the realm of fuel properties for the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Co-Optimization of Fuels & Engines (Co-Optima) effort. Co-Optima is a DOE initiative investigating fuels and engines as dynamic design variables that can work together to boost efficiency and performance, while minimizing emissions.

“I’ve been trying to increase the amount of publications we’re putting out,” she said. Although she is in her laboratory less frequently because of her new responsibilities, she is still involved in fuel combustion research. Fioroni believes in the mission. “We’re looking at different [fuel] blendstocks that could replace petroleum in gas or diesel.” The goal is clear. “We want to understand their auto-ignition properties so we can find something that’s as good as, or better, than ethanol.” Additionally, her team is seeking blendstocks that might be cheaper to make or do not come from a food-source grain.

While she does admit to being a bit crazy in pursuit of extreme races, there is a reason—one that parallels her scientific quests. “It’s kind of fun to push yourself through the challenge,” she said. “You also go through cycles: ‘I definitely can’t do this.’ ‘I’m going to do it somehow.’ It’s always an adventure,” she explained.

For instance, Fioroni was in sight of the 2013 Boston Marathon finish line, about to complete her 50th state marathon in her native Massachusetts, when runners suddenly stopped. In the ensuing chaos, she learned that bombs had exploded, unleashing tragedy—shrapnel narrowly missing her waiting family. Shaken but unbowed, she finished the run the following year.

Once she had conquered the marathon world, her horizons expanded. In August 2015, she found herself struggling in her inaugural Leadville Trail Run, a rocky 100-mile route that crosses a 12,600-foot Colorado pass twice after climbing more than 3,000 feet to the summit. "The first 40 miles I spent throwing up," she said. "I almost quit at mile 13 and was sure I was quitting at the 50-mile turnaround." Urged on by her pacer, Fioroni gutted it out, her headlamp bobbing in the darkness. Somehow, she moved up 227 slots en route to a 169th-place finish. She may have been toughened up for the ordeal by the ridiculous 314-mile Vol-State ultramarathon she had completed over seven days in Tennessee’s July mugginess, featuring “hot, miserable weather and bad hotels.”

Despite—or maybe because of this—she continued.

Twice she was thwarted on ultra-runs in the Andorra region of Spain. In 2015, she recalled that “sleep deprivation caught up with me at the 100-mile aid station,” ending her bid. Three years later, she was making progress with ease through the first 100 kilometers when a freak hail storm caused organizers to evacuate the course. Last year, she finally succeeded there, running Eufòria with a teammate in the Colorado-like landscape. “It took us 106 hours—and 31 minutes,” a span that included less than eight hours total of sleep, sometimes grabbed in 15-minute naps on the ground—a necessity because the event cutoff for runners was 110 hours on the course.

Always driven, Fioroni is particularly proud of NREL’s capabilities and expertise in her field. “I work at NREL because it is a state-of-the-art facility and the people who work here are both a pleasure to work with as well as some of the brightest scientists in the world. I enjoy the collaborative environment that NREL fosters.”

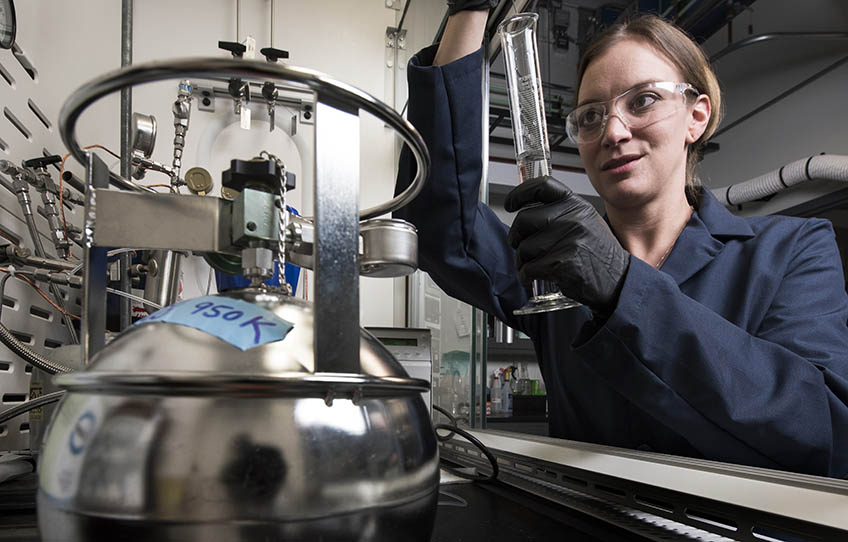

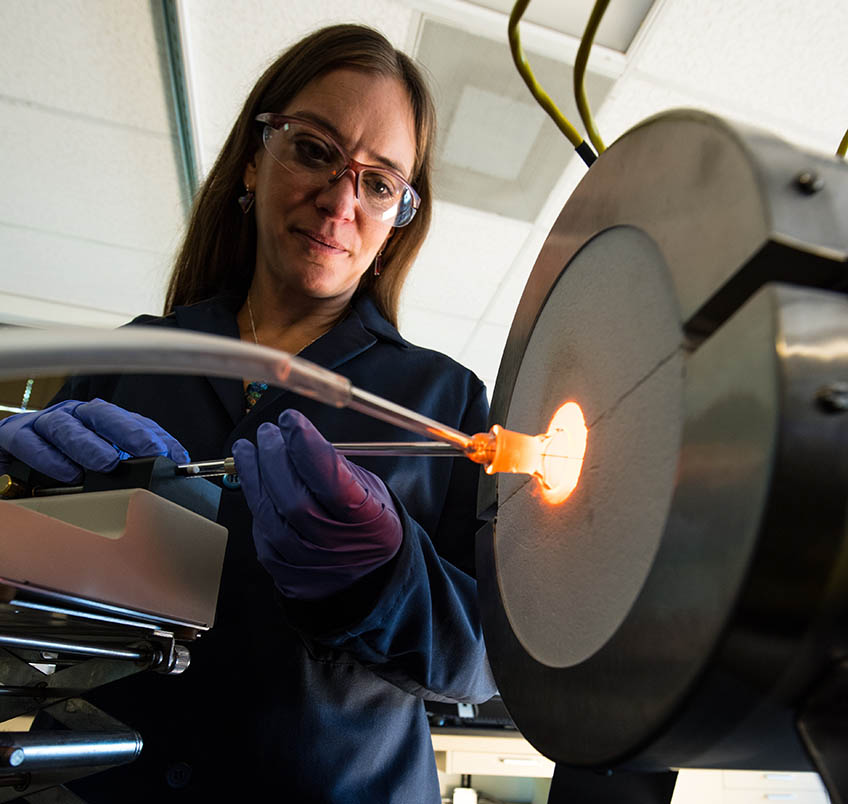

“We have some specialized equipment, including a differential scanning calorimeter/thermogravimetric analyzer hooked to a mass spectrometer to look at the evaporation effects of ethanol (and other alcohols) on gasoline,” she said. “We really are the only people really looking at this, at least for the moment.”

Fioroni explained that ethanol can affect the evaporation of different components in the gasoline and this can be related to cold start in the engine, warm weather drivability, and particle emissions. She also noted that NREL employs a flow reactor that “we use to investigate kinetic mechanisms and soot precursor formation that has led to many collaborations within and outside of NREL.”

Yet capabilities are not the only draw to NREL. “I’m not going to complain about NREL’s location in Colorado, as it is ideal for my active lifestyle. I enjoy hiking and skiing as well as ultrarunning.” Endurance pursuits fit her personality and her professional life.

Outside the lab, her motor keeps revving up. After five years of trying to gain lottery entrance into the iconic Western States 100, she was accepted into the annual June run, which begins in Squaw Valley, California, and ends 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California. Fioroni was eager to test herself in the event.

“You start by going up the ski mountain as the sun is rising, and fog is on the fields. It’s really amazing,” she said. And although she encountered a few logistical hiccups—once missing her support team for a handoff at an aid station—she reveled in the journey. At one point, a famed ultrarunning champion high-fived her as she passed, beaming.

But the true highlight may have come as she chugged up Devil’s Thumb, an aptly-named landmark that few relish after passing through searing canyons. As she progressed, a race official shouted, “How’s it going?” Her response was instant. “I heard you have popsicles at the top.” The incentive proved correct. “All I wanted was that Otter Pop,” she recalled—and relished the frozen confection as she headed toward the finish. As she took the final lap on a high school track, with fans cheering and music playing, she “became emotional.” It had taken her 28 hours, 10 minutes, and “something” seconds—nowhere near the elite mark. But for Fioroni, it was a personal high.

Spurred on by that experience, she’s gunning for what is called the “Grand Slam of Ultrarunning,” which requires completion of four select 100-mile runs in a single year. Fioroni is already signed up for the Leadville race and is waiting to hear from some others that have her on waitlists.

“Maybe I should have ‘slammed’ last year,” she mused, “but I hope this works.” She has tapered off of most marathons. “I’ve run a couple here and there. Usually, I do more trail stuff. I’m slowing down though,” she laughed.

The Future of an Intellectual Adventurer

She’s in it for the long run, but not for glory. “There are people in their 60s running ultras. I think that would be cool,” said the 42-year-old. Her enthusiasm is catching. A frequent training partner is engineer Stuart Cohen of the laboratory’s Strategic Energy Analysis Center. He contacted Fioroni in 2014 after reading an NREL profile about her and realizing that they both had completed the Run Rabbit Run 100 in Steamboat Springs. “He sent me an email saying that we both had been the last two finishers of the race,” she said. Since then, they have both crewed for or paced one another on long events.

The mental health benefits are tangible. “The good thing about running is it is time to be alone with yourself, to clear your head,” she said. “The rest of the day is stressful. I’m always running around. There’s always something. I have lists of lists everywhere. If I’m free, I go to a list somewhere and find something that needs to be done.”

And as she continues on the collective quest for better fuels, she intends to fuel others’ achievements. “I want to be a better mentor to the people who are on projects I oversee. I want them to enjoy” the pursuit.

As always, Fioroni will make lists for her tasks in the laboratory and lists for supplies in her runs. Still, each adventure is new, and Fioroni is aware of reality, a realization that stretches back to her girlhood: nothing ever goes the way you think it will go.

“So just be prepared for anything,” she said. “That makes it fun too. You never know what you’re going to come across.” Her approach will stay the same when life throws her a curve or a leg cramp. “You have to get through, and you just find a way to do it. So when other things happen in your life, you’re like ‘Oh. How do I deal with this? I’ll figure something out.’”

As for people who question the extreme endurance events, Fioroni quoted fellow ultra-athlete Cohen, who once said that ultrarunners are no different than others in their quirks. “Stuart said, ‘We are all a little crazy in some way or another.’ That’s the truth.” Fioroni has heard from plenty of skeptics. “I always have people saying what I do is crazy,” she said. But the journey is what she wants to do. Extreme challenges are all part of the plan one cannot plan for.

“One of the things I enjoy most about working at NREL is the variability of my work, as well as the difficult problems that I want to solve—like a challenging puzzle. It wouldn’t be so rewarding if it was easy right?” she laughed. And once Fioroni finally crosses a finish line, she knows there is always another, beckoning her on.

Learn more about NREL’s fuels and combustion research.

Last Updated May 28, 2025