Ocean Energy Is Almost Ready,

But It Needs a Boost Over the Testing Barrier

How Robust Facilities, Like NREL's, Could Shrink the Chasm From Data to Demonstration

March 5, 2025 | By Caitlin McDermott-Murphy | Contact media relations

This article is the first in a "Found at Flatirons" series that showcases the various technologies at NREL's Arvada, Colorado, campus.

In a large room with concrete-block walls, a crane lifts what looks like a miniature lunar lander out of a water tank. Water drips from the metal contraption as the crane slowly lowers it onto the floor. Then, the clock starts ticking.

"My colleagues and I were like, ‘OK, as soon as it touches the ground, were going to do this and this and this," said Brittany Lydon, a mechanical engineering graduate student at the University of Washington.

Lydon, who likens that moment to a race car pulling up to have its tires changed midrace, will not be sending her machine to the moon. But she is prepping it for a similarly harsh environment: the ocean.

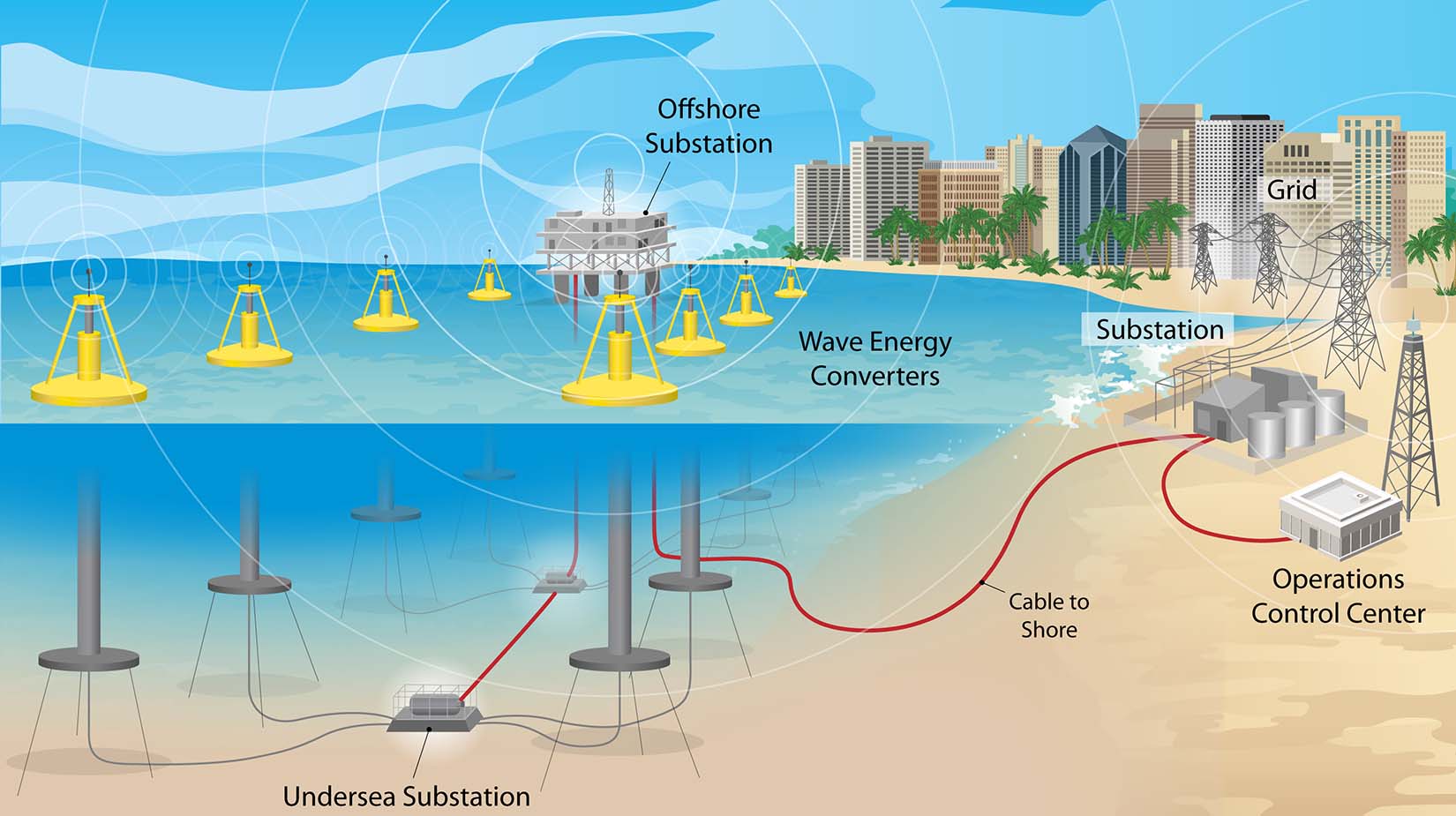

An artist's impression of a wave energy farm illustrates how ocean energy technologies integrate with the larger power grid. Illustration by Alfred Hicks, NREL

Lydons device is designed to harness wave energy, which is a type of marine energy, an early-stage, tricky-to-harness renewable that flows through the currents, tides, and other motions of our oceans and rivers. The United States has enough marine energy pulsing in its waters to meet about 60% of the countrys electricity needs. We cannot capture all that energy, but even a little could help energize offshore industries (like seafood farms), give coastal and island communities the power to weather outages or natural disasters, and help the country reach its energy goals.

However, the marine energy industry needs custom facilities and instruments to vet their novel tech. Researchers studying solar panels can prop a new prototype in a sunny field to see if it works, but tossing an untested marine energy device into the ocean is a bit like hopping into an experimental space shuttle and hitting the ignition.

"You could argue that, in some ways, space exploration is actually easier," said Ben McGilton, an electrical engineer at the U.S. Department of Energys National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) who studies marine energy technologies. "In space, conditions like gravity, radiation, and vacuum are relatively predictable, whereas the oceans ever-changing waves, currents, and corrosive saltwater can create unforeseen challenges that are nearly impossible to simulate perfectly."

Marine energy developers often start with a functional theoretical design. But even the best virtual designs cannot account for every invisible defect or ocean oddity. Developers need a lab-sized ocean to test those theories before they head to the big blue.

That is why Lydon and her colleagues recently found themselves kneeling on wet concrete in NRELs water power facilities in April 2024. A cable on their wave energy prototype was tugging on the device, potentially warping their experimental data. Out at sea, that kind of flaw would have been invisible—just a rogue cable hidden beneath the murky waves—and, even if the defect was spotted, it could take weeks to fix.

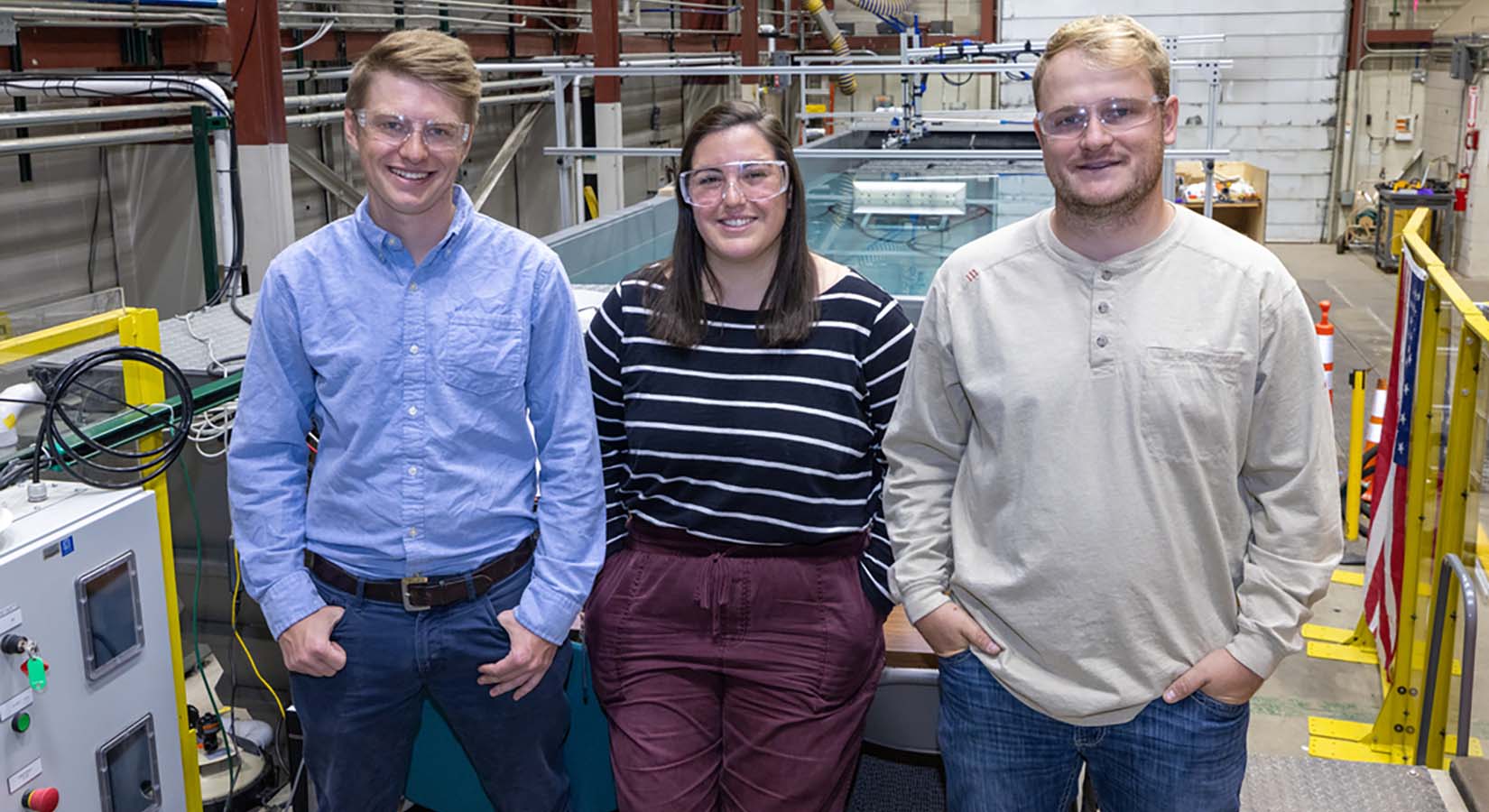

From left, NREL Research Engineer Charles Cando, University of Washington graduate student Brittany Lydon, and NREL Research Technician Kyle Swartz finish their wave tank tests for the University of Washingtons oscillating surge wave energy converter device at NRELs Flatirons Campus. Photo by Gregory Cooper, NREL

At NREL, Lydon and her team needed just 10 minutes to reconfigure their prototypes wiring before a technician lifted it back into a wave tank (located inside the Sea Wave Environmental Lab—or SWEL, for short) for further testing.

"It went as smooth as we could have ever wanted," Lydon said.

Today, NRELs desert facilities offer the comprehensive, computer-to-ocean testing that marine energy researchers and developers need to get their technologies closer to commercial use.

But even NREL did not always have such a bounty.

Between the Data and the Deep Blue Sea

Scott Jenne, a marine energy researcher at NREL, refers to the jump from computer simulations to the open ocean as "the leap of faith. Basically, you go from numerical simulations to, ‘Hey, were going to build a thing and put it in the ocean and hope everything works."

And even if every piece of the device functions just as expected, the ocean might not.

"Theres a well-known saying in marine energy that the 1-in-100-year wave will happen the first week you deploy," McGilton said.

But a leap of faith is not the only way to get from the computer to the ocean. NREL has bridges.

In 2021, the laboratory installed its first wave tank at SWEL, which can simulate scaled ocean waves representative of different sites around the world. In 2023, the facilities welcomed another ocean mimic, called the large-amplitude motion platform (or LAMP), which can replicate even larger ocean motions without even a drop of water.

The laboratory also has machines called dynamometers that can test a devices electrical elements, 3D printers and other rapid manufacturing tools that can quickly churn out new parts if one breaks, and virtual systems that can hook up to actual hardware while simulating different device components, ocean conditions, and even electrical grids.

With all that, researchers and developers could, for example, assess how their device might function in winter waves off the coast of Hawaii, examining how much strain waves might put on their tech or how much energy they could produce for the local grid. And they can do all that without the time, risk, and costs associated with an actual ocean deployment.

—Ben McGilton

"Any time you go to test in a river or the sea, it costs an absolute fortune, and there are so many risks and uncertainties," McGilton said. "Its essential that we have lab facilities that can validate and test the performance before we go anywhere near the water."

McGilton's colleague, Jenne, would agree: He has experienced both options.

The HERO on the LAMP

In 2020, Jenne and a team of NREL researchers started building a hero—or rather, a HERO WEC, which stands for hydraulic and electric reverse osmosis (HERO) wave energy converter (WEC).

The name fits: This kind of device could be a hero for some communities. The wave-powered machine is designed to produce clean drinking water from salty seawater, which could be critical for communities that lose power and access to potable water after a natural disaster.

In 2022, Jenne and his team deployed their HERO WEC prototype in the waters off North Carolinas Outer Banks. But the ocean did not cooperate.

"In that two-week period, we really only saw roughly two-ish useful wave conditions. It was dead flat for the rest of the deployment," Jenne said.

Luckily, they could turn to an ocean imitator for help.

In 2023, the team was the first to mount their device onto NRELs new LAMP, a long-legged metal platform that resembles something out of "Star Wars." There, they could subject their prototype to almost any kind of wave motion without worrying about storms or dead waters.

NREL's LAMP tests prototype devices to improve designs before deployment in ocean waters.Photos by Joshua Bauer, NREL

"Theres still a reason to do those ocean deployments," Jenne said. "You learn stuff there that you'll never be able to learn on LAMP and vice versa. But having that controlled test facility where you can literally turn the waves on and off when you need them is so valuable."

During their LAMP test, the HERO WECs drivetrain "locked up and snapped the mooring line," as Jenne described it. But, like Lydon and her team, the crew simply shut the LAMP down, came up with a solution to prevent it from happening again, and resumed testing within a couple days. For comparison: Just six hours into a recent Outer Banks deployment in 2024, a rogue storm knocked the HERO WEC around, causing a winch to cut a cable. But no one could reach the device for two weeks.

"You spend a huge amount of money to understand maybe a few ocean conditions," Jenne said. "Versus LAMP—we ran over 100 different cases in a month."

That is why Lydon and her team came to NREL. They too were searching for that data wealth. Only, they turned to a different instrument.

Swell Data From the SWEL Wave Tank

Lydons wave energy prototype looks nothing like the HERO WEC. Her groups device is designed to generate electricity by swaying back and forth, like sea grass, in ocean waves. Although her institution, the University of Washington, has its own wave tank, it is about 2.5 times smaller than NRELs. Their small-scale prototype could barely fit, and the team was concerned its proximity to the tanks walls could create ricochet waves that might not exist in the real world, skewing their data.

"That brought us to the point of having this system functional but not having a good place to test it," said Brian Polagye, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Washington and Lydons advisor. "And thats where SWEL came along."

SWELs tank is big enough to handle prototypes about 1/75th the size of a full-scale device. Through the tanks one glass side, researchers can watch how their device handles waves both above and below the water (the oceans often murky water prevents this kind of up-close study). And if human eyes are not powerful enough to spot an issue, the tanks motion-tracking cameras and various sensors likely are.

With support from the Testing Expertise and Access for Marine Energy Research (TEAMER) program, funded by the U.S. Department of Energys Water Power Technologies Office and administered by the Pacific Ocean Energy Trust, Lydon spent several months at SWEL during the spring of 2024. There, Lydon and the team could test how their device performed in a larger range of potential wave conditions.

"We were able to get a ton of data in a relatively short amount of time," Lydon said. "That has been huge in trying to answer our questions but also forming new questions." But if Lydon had to describe her experience in one word, she would say it was boring, "which is what you want." Boring means nothing went awry; boring equals success.

"We had what we needed, and we were given everything to do it," she said.

The Recipe for Advancing Marine Energy

Over the past few years, NRELs water power facilities have grown to offer what NREL Water Power Technology Validation Manager Rebecca Fao often calls a "soup-to-nuts" service. At the Flatirons Campus, people can model their novel designs with the laboratorys award-winning software, manufacture a prototype, test a specific component or the entire device, manufacture an improved or larger prototype, and hook actual hardware up to virtual grids or oceans that can mimic real-world conditions.

—Ben McGilton

"We can test whole systems and see how they would interact with a microgrid, small community, or even the grid—and not just simulated but with real voltage and currents," McGilton said. All this support can, as McGilton puts it, "improve the overall chances of success."

But none of these machines or models function without people.

"One of the reasons that these experiments, even the initial experiments, were so successful is the support and flexibility of the staff," Lydon said.

From modelers to technicians to electrical and mechanical engineers, NRELs team of experts are perhaps one of the laboratorys greatest assets. If a device malfunctions, they are there to troubleshoot, diagnose, repair, or even operate a crane.

Of course, NREL might have a suite of swell equipment, but it does not have everything. The U.S. Navy has an indoor ocean (also known as the maneuvering and seakeeping basin, or MASK) that holds 12 million gallons of water (SWEL holds only 13,000). A new wave energy test site, called PacWave South, where researchers and developers can test full-scale devices in the open ocean, is under construction off the coast of Oregon.

Because the United States has so few of these facilities, collectively, they are critical for the marine energy industry to advance quickly. "Its all a big, interconnected ecosystem," said Polagye, Lydons advisor.

That ecosystem is growing thanks to renewed interest in this lesser-known renewable. And, in part because of facilities like NRELs, the field has made significant leaps in the last 10 years.

"Its been a fascinating decade," Polagye said. "And I think the next will be just as fascinating."

Want to learn more about NRELs Flatirons Campus? Stay tuned for the next feature in our "Found at Flatirons" series. Remember to sign up for the water power newsletter, too!

Share

Last Updated May 1, 2025