Hats Off and Happy Trails to NREL Wind and Water Pioneer Bob Thresher

From his trademark black hat to his legendary one-liners and singing contributions to the Wind Weenie Wailers, Research Fellow Bob Thresher undoubtedly cuts a memorable, larger-than-life figure.

When asked to describe him, Thresher’s colleagues label him as everything from “pioneer” and “mentor” to “friend,” “hero,” and even “rock star.”

From “Budget Rent-a-Prof” to Man in the Black Hat. Meet Bob Thresher. Photo by Dennis Schroeder, NREL

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Water Power Laboratory Program Manager Al LiVecchi described Thresher’s “famous look of willful abandon when he cranks up his Subaru and metal music starts blaring from the stereo as he hurls the group to the lunch spot.” Which, as LiVecchi pointed out, “is always entertaining when new interns and job candidates are in the car!”

Everyone loves a good story—and several have been written about Thresher over the years—which begs the question: What has not yet been said about him and his time at NREL?

As he looks toward retirement and shifting to an emeritus position at the lab, we sat down with the wind and water pioneer to find out.

Believe it or not, it was a single phone call that launched Thresher’s storied career at NREL.

Thresher found himself at one of those existential forks in the road during the 1973 oil embargo, when the goal of achieving U.S. energy independence loomed large.

“What motivated me was sitting in a gas line, waiting to get gas, and I got pretty angry about that and decided that the first chance I got, I would try to do something to get us off foreign oil,” he said.

There were not many people working on wind in the 1970s, Thresher said. He was involved in the early planning of the federal wind program under President Richard Nixon and eventually went to work at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), called ERDA in the early days, or the Energy Research and Development Administration.

“I was the kid. I was referred to as the ‘Budget Rent-a-Prof,’” Thresher said.

He was burning the candle at both ends, doing consulting work on wind and carrying out research for DOE, all while working as a professor at Oregon State University—and something had to give.

Bob Noun, then the group manager for the wind program at the Solar Energy Research Institute (SERI), the laboratory that would later become NREL, had been trying to lure Thresher to SERI for some time.

“Bob had already developed a national reputation in wind research, and because of that reputation, he was simultaneously being pursued by the DOE’s small wind turbine test center at Rocky Flats, managed then by Rockwell International,” Noun said.

Noun’s numerous attempts to bring Thresher into the fold were seemingly in vain, each bid met with Thresher replying that he was content teaching in Corvallis, Oregon.

Noun, however, had a plan afoot.

Thresher was grading final exams when he received that fateful call from Noun that forever altered his course.

“It occurred to me: When is the best time to entice a professor to leave academia? It’s when they’re grading finals, the worst week of the semester for every college professor,” Noun said.

“I waited until I knew it was a dark, rainy day in Corvallis and got him on the phone, just as he was 'wondering whether any of my students had learned anything this semester!’” he said.

Noun offered Thresher an interview and the opportunity to come visit SERI.

Thresher accepted Noun’s invitation to tour the campus, meeting SERI Director Harold Hubbard during that auspicious first visit.

“He signed on to the lab a few days later,” Noun said. “The Thresher era had begun.”

A Tiny Budget and a Big Dream

It was 1984, the heart of the Reagan years, when Bob joined SERI.

Thresher joined the five-person wind team at SERI in 1984 and the rest, as they say, is history. Photo by Warren Gretz, NREL

Thresher recalls that when Bob Noun brought him to SERI, there were but five employees in the wind program; but the subsequent unification with what had been the Small Wind Energy Center at Rocky Flats brought the number of researchers up to about 40.

Thresher, as he described it, essentially joined a salvage mission, the overarching goal of which was to save what they could from the once-extensive wind program and sustain it through those lean years.

Dr. Hubbard, or “Hub” as he was usually called, had a relaxed management style. His ability to build relationships during that difficult time left a lasting impression on Thresher.

“Hubbard was an approachable director. He managed by walking around and talking to people,” Thresher said. “He would walk into people’s offices and sit down and put his boots up on your desk and ask, ‘Ok, what are you doing? What’s going on?’”

Thresher took these informal management lessons to heart, as he became the kind of universally respected manager and mentor he is known to be today. One does not have colleagues lining up to say the kinds of things they have said about Thresher otherwise.

NREL’s Wind Laboratory Program Manager Brian Smith said, “Bob Thresher is my hero. He taught me to trust science, be passionate about what I believe in, and enjoy people and life.” Former NREL Wind Laboratory Program Manager Susan Hock described her years working alongside Bob as, “the most wonderful part of my career.”

Much like Hubbard, Bob’s door is always open; the overflowing candy bowl on his desk giving passersby an excuse to stop in and talk about whatever happens to be on their mind.

“Sometimes when looking for guidance, I have gone into his office eight-plus times during the day and every time a different person is there discussing their work,” LiVecchi said. “Things just seem to be clearer and make more sense after you have a little session with Bob, who is ever the professor.”

From Wind to Waves

Although he started his career in wind, Thresher is considered a pioneer in both the wind and marine energy industries. How he made that jump from wind to waves has a lot to do with his love of the unknown.

“I love the early stages of sorting out ideas—what’s going to work and what’s not going to work—and trying new things,” Thresher said.

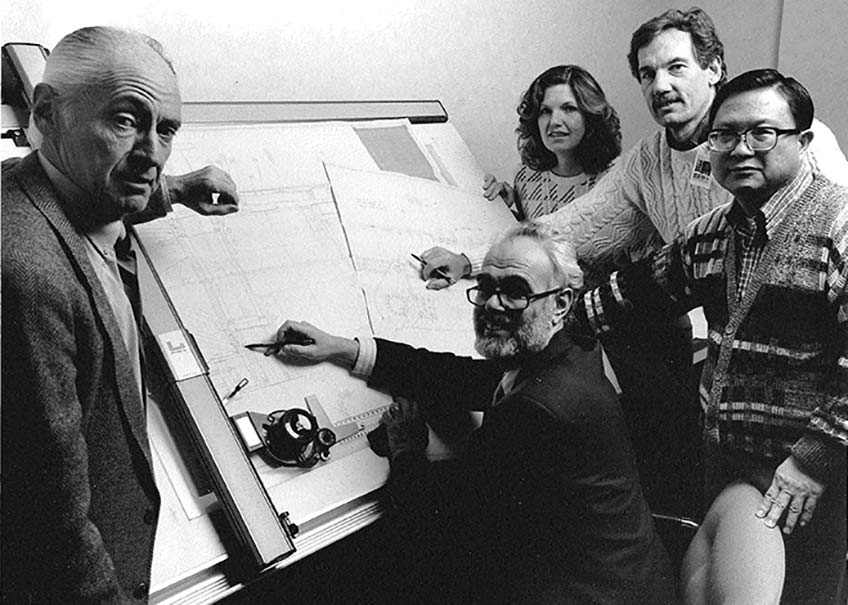

SERI wind energy pioneers at work: (from left to right) Palmer Carlin, Bob Thresher, Susan Hock, Darrel Dodge, and Peter Tu. Photo by Warren Gretz, NREL

“He’s had an imprint on the entire marine energy portfolio,” LiVecchi said.

While it enjoyed a strong start in European countries, U.S. marine energy in 1973 largely consisted of ocean thermal and energy gradient technologies, according to Thresher. And though wave and tidal research remained popular across the pond, it was mainly phased out in the United States around 1994.

It was not until 2008 that Congress allocated funding for the DOE to launch a water power program.

Thresher and colleague Walt Musial were instrumental in getting the NREL water power program off the ground.

“In 2008, we worked side by side to win the DOE lab call for the first round of funding, which started the marine hydrokinetics and water power program,” said Musial, NREL’s offshore wind lead.

Though it holds significant promise, marine energy in the United States is still in the early stages of research and testing devices, “where wind was back in 1985,” Thresher said.

For example, while the cost of land-based wind energy in the Midwest is now “as low as 1.8 cents/kilowatt hour (kWh), offshore wave energy is estimated to be between 75 cents and $1, while tidal energy is nearer to about 25 cents,” he said.

Thresher is all smiles standing in front of the Ocean Energy Wave Energy Converter at the Vigor Shipyards in Portland, Oregon, in spring 2019. Following its construction, the device was later shipped to Hawaii for validation at the U.S. Navy’s Wave Energy Test Site on Oahu. Photos courtesy of Bob Thresher

Enthusiastic and energetic innovators are working on technologies such as tidal turbines and wave energy converters to turn the tide, so to speak, and NREL counts many such innovators among its ranks. Water Power Program Mechanical Engineer Nathan Tom is one of them.

One of his favorite moments at the laboratory was listening to Thresher’s presentation on the history of wind turbines. “Hearing about the early wind days from Bob helped me to understand that we don’t know how the technologies being developed at NREL will take form in implementation, but if we don’t try, we’ll never know what could be,” he said.

Inspiring tomorrow’s energy innovators through the power of what could be: Thresher's list of appreciative mentees is extensive, including Nathan Tom (shown here). Photo by Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Breaking Through Limitations

On Thresher’s watch, wind energy experienced a remarkable growth trajectory, and his experiences in the industry hold valuable lessons for marine energy.

Hock described how she and Bob worked so closely together in the early days of the wind program that colleagues often referred to the inseparable pair as “Bobby-Sue.”

She looks back on the early work of the ‘80s and ‘90s fondly. “We partnered with DOE to foster tremendous breakthroughs, both in the performance and the cost of wind turbines. I will always treasure the great adventure we had,” she said.

It was during this same period that Bob hired Brian Smith. “When Bob hired me into SERI in 1988, the U.S. wind industry was in transition, U.S. wind companies were struggling, and the technology was not reliable,” Smith said. “Bob initiated the Advanced Wind Turbine Research Program focused on science and technology innovations that shaped the wind industry of tomorrow.”

This pivotal program laid the foundation for wind energy’s meteoric rise. “Decades later, elements of this program are embedded in wind energy research worldwide and helped drive the United States to achieve over 100 gigawatts of installed capacity and launch into the new offshore wind frontier,” Smith said.

Thresher and Former Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary (far left), her aide, and prominent early wind consultant and turbine developer Bob Lynette (far right) visit with Thresher at the NREL wind site during its designation as the National Wind Technology Center in 1994. Photo courtesy of Bob Thresher

The sky, if that, is the limit for wind and renewables, according to Thresher.

From those humble, early years, when “most research turbines were paid for by DOE as experimental devices,” according to Thresher, it is hard to believe that the U.S. wind industry is now on track to achieve—and likely exceed—the goal of 20% wind-generated energy by 2030.

“Around the year 2000, it became obvious that wind would make it, somehow, as part of the generation mix,” Thresher said. Wind energy currently claims the largest installed renewable energy capacity in the United States.

In Thresher’s estimation, part of wind energy’s success is owed to the practice of what he describes as “creating vulture bait.”

The phrase refers to smaller operations capturing the attention of the major players in the industry. “When the time was right and the costs were right, the big companies would jump in and grab the bait and go with it,” he said.

Major industry players such as General Electric and Siemens saw this type of potential in wind and decided to invest around the turn of the century—and innovation flourished.

“We [wind researchers] were very successful in creating vulture bait. This needs to happen again for the wave and tidal industry,” Thresher said. “We’re not close enough yet.”

Text Version. Thresher on the importance of working with small businesses to spur new innovation in the wind and water power industries.

Unparalleled Opportunities at NREL

For a man who likes to be lost “because that’s the fun part,” Thresher sure has managed to find his way in the world of wind and marine energy during his nearly 40 years at NREL. “He was truly the driving force that lifted the NREL wind program to the worldwide stature the program enjoys today,” Noun said.

Looking back on his tenure at the lab, Thresher counts the development of the National Wind Technology Center at the Flatirons Campus among his proudest achievements.

Thresher championed the establishment of the world-renowned National Wind Technology Center at the Flatirons Campus, which sprouted from humble beginnings as the small wind turbine test center on the former Rocky Flats site. Photo by Josh Bauer, NREL

It is hard to believe that the now-sprawling, 305-acre Flatirons Campus grew from little more than a small wind turbine test center in 1978 into the nation’s premier wind energy, water power, and grid integration research campus today.

“It was really important in the early ‘90s to be a national center. It set NREL up as a leader in wind energy,” said Thresher, who served as director of the National Wind Technology Center from 1994 to 2008. “It was the establishment of Flatirons Campus and the expansion of that campus into a multitechnology center that will allow NREL to expand its mission, too.”

When did Thresher realize he would stay at NREL for the long haul?

“Gee, I never did!” he said with a laugh.

In all seriousness, he thought he might stick around for maybe 5 years and then move on.

Thresher, as director of the National Wind Technology Center, welcomes then-Secretary of Energy Federico Peña to the campus in 1997. Photo by Warren Gretz, NREL

He came to realize that NREL offered unparalleled opportunities by way of the technology and the ability to work with both industry and government.

Thresher sees the national laboratories, such as NREL, as uniquely positioned to hatch the new ideas and concepts that drive the industry forward.

“I think labs are at their very best when they’re sorting out new concepts and new ideas, trying to get things focused on a path or several paths that lead to successful technology that could be commercialized,” Thresher said. “As time went on, I just didn’t see a place where I could have a bigger impact or change the way we produce energy any more effectively than at NREL; we’re looking to do good and make things happen, so it’s kind of an altruistic opportunity that, to me, just is not available any place else.”

Bob's Parting Wisdom to Newcomers and Old Friends

"We are in a period of dynamic evolution, socially and technically, regarding energy production and use. Over the next several decades, we will likely see a total transformation of how we generate the energy we use in all aspects of our life, from providing for our human comfort, to growing our food, to powering our transport systems and manufacturing processes. The energy we generate, and the processes used to produce our material goods, needs to be accomplished without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

"This total energy transformation will require innovative, cross-disciplinary solutions employing all aspects of science, including social and environmental science, together with sound engineering and implementation know-how.

"My parting advice to my NREL colleagues, both young newcomers to the lab and longstanding friends, is to take every opportunity to engage with each other across the diverse disciplines at the laboratory to learn the new skills needed to evolve this total energy transformation.

"NREL is perfectly positioned with the right scientific, engineering, and implementation expertise to make a sustainable energy future happen. We just need to work together and learn from each other to be able to create the new technologies and processes needed to make our way of life totally sustainable."

Robert Thresher, June 2020

Once a Teacher, Always a Teacher

Throughout his time at the laboratory, Thresher always strove to be a good teacher, a good manager, and a good partner. From providing heartfelt guidance to plucky one-liners, a long line of appreciative mentees and colleagues can attest to his achievements in this realm.

LiVecchi recounted Bob’s attempts to make sense of sometimes-arcane required tasks, likening them to “awkwardly putting something into somewhere it probably shouldn’t be, sometimes while standing in a hammock.”

NREL researchers Jason Jonkman, Robert Thresher, and Robynne Murray stand next to a water blade at the Flatirons campus. Photo by Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Thresher’s decades of experience have afforded him a unique perspective, allowing him to soar above the treetops and not get lost in the brush below—and he does not keep that hard-earned wisdom to himself.

“Often, as a young researcher, the one-to-two-year time frame seems like a long time, and not having past knowledge makes it difficult to see the larger trends at work,” Tom said. “I’ve really appreciated Bob’s recommendations to not get too worked up on program changes or challenges. We just need to focus on producing the best work we can do at the moment, and that will keep the lab successful and make the greatest impact.”

Among the many lessons Bob has imparted is the importance of having a good laugh. “Bob was not only the smartest guy in the room at meetings—but also the funniest,” Noun said.

Noun recalled a time in the late 1980s when he and Thresher were attending a program review at DOE headquarters in Washington, D.C.

“The DOE manager was sternly lecturing us on how bad we were performing on some project,” Noun said. “Bob [Thresher] drew a cartoon of an airplane crashing and burning with the two of us sitting in the cockpit. He handed it to me right as I was about to respond to the critical comments, and I really had to bite my lip from laughing in this otherwise tense exchange,” he said.

And Thresher’s sense of humor has carried many colleagues through choppy waters over the years.

“The thing I love most about working with Bob is his sense of humor and his laugh. Even when we have a hard task in front of us, with technical challenges, he has a way of brilliantly coming up with technical solutions while keeping you smiling and laughing,” said NREL Water Power Researcher Robynne Murray. “He puts things into perspective to help me not let bumps in the road stress me out. He taught me to be patient but persistent.”

In a sense, one might say Bob has come full circle.

“I really enjoy being a mentor and a teacher,” Thresher said. “I started out at Oregon State as a teacher, and I feel like I’m still a teacher.”

And NREL researchers, and those in the wind and marine renewable energy fields, are all the better for their time spent learning alongside Bob Thresher.

The Thresher Era

1970: Bob completes his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from Colorado State University and accepts a position as assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Oregon State University

1973: Bob begins his first wind energy research project for local Oregon People’s Utility Districts

1976: Bob begins a two-year assignment with the Energy Research and Development Agency (predecessor to DOE, which was created in 1977) as a “Budget Rent-a-Prof” in Washington, D.C.

1978–1984: Bob returns to Oregon State University and begins research on wind turbine dynamic response to wind turbulence and serves as a consultant to early wind companies, including Boeing, Hamilton Standard, U.S. Windpower, Atlantic Orient Corporation, Northern Power Systems, and others

1984: Bob leaves the university to join the Solar Energy Research Institute as principle scientist

1990: Bob receives the first H.M. Hubbard Award

1992: Bob receives the American Wind Energy Society Federal Programs Award “for effective management and leadership”

1994: NREL’s National Wind Technology Center is created by Hazel O’Leary, secretary of energy, at the current Flatirons Campus location south of Boulder, Colorado

1994–2008: Bob serves as director of the National Wind Technology Center

1997: Bob is named the American Wind Energy Association’s Person of the Year

2001: Bob receives a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Wind Energy Association

2004: World Renewable Energy Network presents Bob with the Pioneer Award

2008: Bob is appointed NREL research fellow; he and Walt Musial secure DOE funding for NREL’s Water Power program

2010: Bob is named an Innovator in Wind Power by Windpower Engineering magazine

2014: Bob works with the wind energy research community to form and serve as the launch director of the North American Wind Energy Academy (NAWEA), which brings together researchers, educators, and industry members to advance collaborative wind energy research

2020: Bob retires after 36 years at NREL and becomes an NREL researcher emeritus.

Learn more about NREL's water research and wind research.

Last Updated May 28, 2025