Behind the Blades: How Cris Hein Helps Bats and Wind Turbines Share the Sky

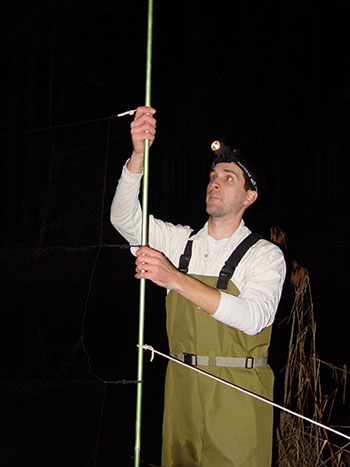

Photo by Cris Hein; graphic by John Frenzl, NREL

Like most everyone, Cris Hein thought all bats were vampire bats. That was 25 years ago, before NREL’s lead environmental scientist began researching the world’s only flying mammal.

Hein always appreciated wildlife. Growing up in the suburbs of Houston, Texas, he liked camping during family vacations and always enjoyed nature shows. But he never dreamed of having a job in wildlife.

While Hein was working on his master's degree in biology, one of his advisors had an opening to do research on bats.

“I jumped at the chance because it seemed really interesting. How many people get to work with bats?” Hein said. “As soon as I started catching, handling, and researching them, I was fascinated by them. And it took off from there.”

Hein ended up getting a Ph.D. studying bats. This gave him the chance to handle and work with several species and discover that each has its own personality.

“Some are sweet and docile, just laying still in your hand,” he said. “Others are feisty, constantly moving and making noise. They try to be intimidating by opening their mouth real wide. So just learning that they’re all different intrigued me.”

Hein also learned that only three of the more than 1,400 species of bats in the world actually suck blood.

We hung upside down with Hein to learn a little more about him and bats—just in time for Bat Appreciation Day, which was April 17. (Please note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

What makes bats worthy of an appreciation day every year?

There are lots of reasons. Most of the bats that we have in the United States eat insects, and a lot of those insects are agricultural or forest pests. And so, bats are important to our ecosystem by keeping insect populations under control. Studies have shown that in the U.S. alone, bats save farmers billions of dollars in pest control every year. That trickles down to lower food prices and fewer chemicals in the environment. Bats also pollinate a lot of the agricultural crops that we enjoy around the world, which is a great ecological service for us as well.

Bats are also interesting. They’re the only mammals that can fly. They use sound echolocation, or sonar, to navigate in dark environments and fly at night. They find places to sleep that are difficult to access, like in caves or trees. And they come in lots of colors. There are bats that are brown, red, yellow, and multicolored. Some bats have stripes, and some have spots.

So they’re not all vampires. What other myths about bats can you bust?

Easy. They don’t fly at you. They don’t attack you. They don’t get tangled in your hair. In fact, bats are secretive animals who don’t want anything to do with us. Also, they spend a lot of time grooming themselves and others in their colony, so they’re not dirty animals.

How did you become involved in wind energy?

I was finishing my Ph.D., writing a dissertation, and looking for paid work. Bat Conservation International hired me to work on a wind energy site that was not built yet. It was still a natural setting, and we needed to determine whether it had bat activity to predict risk once the site was operational. During that project, I helped a consulting firm that was starting their bats and wind energy program and looking for advice. When I finished my degree, that company was looking for a bat biologist. So, I got a job with them and moved to Oregon, where I still live.

Then I was hired by Bat Conservation International to be their director of bats and wind energy. I worked there for eight years before starting with NREL in 2018.

What do you do at NREL?

I manage NREL’s environmental program, which Bob Thresher and Karin Sinclair started at least 27 years ago. I worked with Karin when I was at Bat Conservation International, and NREL funded some of our work. So it was an easy transition for me to work at NREL.

My job is so varied. We research land-based and offshore wind energy environmental issues, and we fund others to do research. We consider how to best site a facility so that it still captures wind energy but also reduces interactions with wildlife.

I work with bats, which is where I feel most comfortable, but we also work with eagles and other species—such as marine animals that might interact with offshore wind energy systems. NREL also has a strong educational outreach and engagement program, conducting webinars and trainings for stakeholders, industry, state and federal agencies, and others.

Can bats and wind turbines coexist peacefully?

We are optimistic that we can create solutions for wind and wildlife to coexist. When you put something like a wind turbine in their space, bats might interact with the structure just because it’s there. But there’s also a behavioral component in which the animals might actually be interested in the structure. So they’re not just flying in the airspace and going from point A to point B. They’re flying around and seem interested in or attracted to the structure, which unfortunately puts them at greater risk.

We've used thermal video cameras to record their behavior and we just see them flying around and around, in and out of the rotor-swept area. And the bats appear to have no understanding that they're at risk. There are a lot of reasons that they might be attracted to wind turbines, but we don't have a definitive answer why. Insects might be in the area, attracting bats who stay around that area because they think it's a good place to forage for food.

We know that bats have been observed roosting in the nacelles of wind turbines and there might be a social component to these locations. When some bats are there, it draws in other bats, and then they're interacting with one another. The greatest period of risk is late summer to early fall when bats are mating and migrating. Males could be chasing other males or searching for females. Females could be searching for males. It’s complex. If we can understand the driver behind what’s going on, it might help us come up with strategies to reduce risk and have coexistence between bats and wind energy or other species and wind energy.

Do bats have an impact on your personal life?

Yes, because they’ve been a big part of half my life—from graduate school to my career. I don’t get to interact with them as much now because I don’t do fieldwork anymore. But I enjoy speaking about bats at elementary, junior high, and high schools. As you can imagine, kids gravitate to bats because they’re so interesting. They can fly. They can echolocate. And they can be funny looking or very cute looking. The students are captive audiences and are always excited to ask questions.

For instance, students ask why bats hang upside down. How come the blood doesn’t pool in their brains? Well, the reason is that hanging upside down allows them to occupy space that no other animal does—like cave walls. Also, it doesn’t take much energy to close their little feet and hang from cave ceilings. All they have to do is let go, and they start flying. In addition, bats’ circulatory systems are a bit different, allowing their blood to flow and not get pooled in their brains like it would for us.

Do you think the environmental work you’re doing at NREL is important?

Bat research has grown so much since I started in the field, in part due to concern about wind energy and about a fungal disease that affects bats called white nose syndrome, which has devastated bat populations in the East and, since moving west, is now in almost every state in the U.S. It’s really sad.

But over time, people’s perceptions of and concern for bats have changed. Everybody’s really engaged in this issue, including the wind energy industry. They want to do the right thing. It’s challenging for them to protect wildlife and also produce renewable energy. A lot of times, this issue can be viewed as the environmental side versus the industrial side. And there’s some truth to that. But we’ve made a lot of progress in this field because everybody has come to the table. I really enjoy the collaborations that have been built.

I think NREL’s environmental program has a good reputation for wanting to solve the issue in a scientifically credible way while meeting everybody’s needs and seeing different perspectives.

What’s the best part of working at NREL?

I get to work not only with other biologists and ecologists at NREL but also with atmospheric scientists, computational scientists, and engineers. It’s really amazing, and I think that’s what makes NREL so unique compared to other organizations.

Learn more about NREL’s environmental science research and the other amazing people behind the blades by subscribing to the Leading Edge newsletter.