Manufacturing Masterminds Q&A With Kat Knauer

Plastics Revolutionized How We Build Things. Now This Polymer Scientist Is Exploring How To Break Them Down To Save the Planet

In May 2022, media outlets reported a staggering statistic: More than 90% of plastics generated in the United States ended up in landfills instead of being recycled. Many people felt like they had been sold a myth on the role that individuals could play in reducing humanity’s collective waste.

“When plastics were first discovered, they were amazing, remarkable materials that people had never seen before,” said Kat Knauer, a polymer scientist at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the chief technology officer of the Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE™) consortium. “They were actually more sustainable solutions to glass, metal, and paper and reduced other types of pollution.”

Thanks to the wide adoption of plastics, vehicles and airplanes became lighter and consumed less fuel; people started storing food for longer periods, reducing food waste; and hospitals had an easier and more efficient way to sterilize tools and packaging, reducing the spread of disease.

However, each type of plastic needs specific conditions to be broken down and turned back into its base materials—called monomers—so that they can be recycled into something new. And this is where we have huge structural gaps between consumer knowledge, local regulations, and access to adequate recycling facilities, Knauer said— resulting in enormous amounts of unexpected waste.

“There’s so much more to plastics than just the garbage,” Knauer said. “Instead of being seen as a massive waste burden, they’re actually these really valuable carbons that can be put back into our economy over and over again.”

That is why she—and the BOTTLE consortium—are working to design better recycling processes and create new, more easily recycled plastics.

“Plastics were kind of designed to last forever. That is the beauty of them; they are lightweight, strong, and cheap, and they do not easily break down. Now we’re in a pickle because of that,” Knauer said. “But we have an opportunity to rethink and redesign these materials to fall apart when we’re ready for them to do so.”

In this latest Manufacturing Masterminds Q&A, Knauer shares how a backyard fire ant invasion led her to a career in science, what a chief technology officer does, and how the BOTTLE consortium is working with Amazon, Patagonia, and other companies to design more planet-friendly plastics. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How did you get into science when you were a kid?

I grew up in Florida, and we had a lot of fire ants in the summers. They are terrible; their bites are really painful. When I was in seventh grade, we put down a pesticide in the backyard to get rid of them, and I was convinced it was making my dog Penny sick because every time she went into the backyard, she would act really lethargic.

Oh no! Poor Penny. What did you do?

Kat Knauer started her science journey with fire ants in Florida. Today, she is tackling a global problem: plastics pollution. “It’s polluting our oceans and our waterways; we have microplastics in our lungs and our blood. It’s virtually everywhere,” Knauer said. Photo from Katrina Knauer

That year for my science fair, I did a project on a sustainable way to mitigate fire ants. We found that instant powdered grits were effective at killing them because they have really high sodium content and the powder expands very quickly in the ant’s stomach. It ended up winning my school’s fair, then the county’s, and then the state’s. That started my science journey because, well, fine … I loved winning awards. And I realized the scientific method is how we can change the world.

I love that. You decided to solve a problem for your dog and ended up solving one for your entire state.

I know. I didn’t care about the pesticides hurting me. I only cared about my dog. Penny lived until I was 25 and in grad school. She was my best friend for 15 years.

Now, at NREL, you’re trying to change recycling, right?

Right. I wanted to work in mitigating plastic waste and making plastics more sustainable. And I figured if I earned a Ph.D. in polymer science, I would be an expert and people would listen to me. Now, with the BOTTLE consortium, we’re trying to develop technologies that can effectively recycle and upcycle today’s existing plastic waste while redesigning materials to be more intrinsically recyclable by design for the future.

What do you do as the BOTTLE consortium’s chief technology officer?

A big part of what I do is bring in strategic partnerships. I came from a relatively successful plastics recycling startup that I helped build in San Francisco. That’s how NREL and I started dating, and then we started going steady three years ago. Now, at NREL, I can help deploy technologies and launch startups into programs like the West Gate Lab-Embedded Entrepreneurship Program and others. So, I think I help bring that entrepreneurial mentality to our research team. If they have something that’s looking really good, let's start a company. Let’s see where it can go.

Every summer, Knauer goes on a weeklong expedition to remove plastic waste from Alaskan waters. The group collects tons of heavy plastic debris (literally) and have picked up rubber duckies, plastic lawn swans, laundry baskets, spatulas, pharmaceutical containers, unopened beer cans, and a whole lot of fishing waste. Photos from Katrina Knauer

How about plastics and manufacturing? How do those two worlds intersect?

Plastics play a major role in our manufacturing community because they’re so integral to everyday products. And the way we manufacture plastics is not terribly energy intensive because they’re very easily synthesized, processed, and remolded.

And while the main ways we make plastics are quite energy efficient, the amount we make and our use of fossil fuels and petrochemical sources are not. That’s one way we’re trying to decarbonize the manufacturing pipeline for plastics. Upstream, can we make biobased or waste-based plastics that are easier to recycle? Downstream, can we create a circular supply chain where we only have to take carbon from the Earth one time?

How feasible is that future? Are we close to achieving those goals?

It’s a very daunting task. If you asked me five years ago, I would have been much more pessimistic. But since then, with the sheer amount of support, funding, and new laws and policies, so much has happened in plastic waste mitigation that we're finally starting to see incentives to implement more circular strategies from companies. Multiple states, including Colorado, are passing laws that mandate that companies be held responsible, financially, for how their products are recycled. That’s not going to solve all our problems, but it’s a step in the right direction.

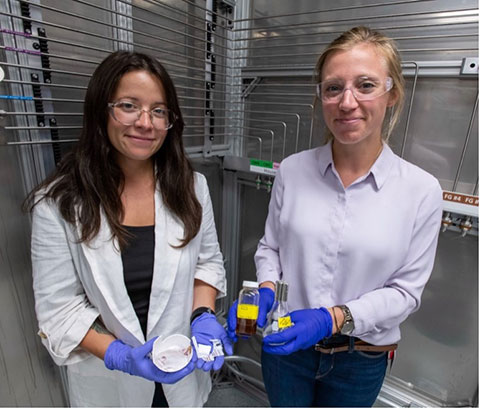

Through the BOTTLE consortium, Knauer (left) is working to redesign plastics so they are easier to recycle and are made from biobased materials as opposed to fossil fuels. Photo by Bryan Bechtold, NREL

NREL also works with companies that want to reduce their plastics waste, right?

Yes. We have a big project with Amazon to pivot their plastic mailer packaging toward biobased materials, which is a huge step in achieving net-zero carbon emissions. But Amazon did not want to make the shift without a recycling infrastructure for biobased plastics. They came to the BOTTLE consortium to see if we could help design a recycling process that could accommodate highly heterogeneous streams of both petro- and biobased plastics.

We’ve trademarked the technology, called EsterCycle™. And one of the postdocs in the group who led the work, Julia Curley, spun this out of NREL into a startup company in the West Gate program. It’s these types of projects that make me feel like there is hope. Amazon is one of the biggest companies in the world. If they are demanding more sustainable materials, odds are the supply chain will follow.

Wow. That’s exciting! Any other neat projects you’re working on?

Every single one gets me so pumped up. We’ve had a wonderful collaboration with Patagonia to build a textiles recycling platform. Our clothing has something like four to eight different components in them. We’re literally wearing plastics on our body, and they’re very difficult to recycle. Fast fashion has resulted in huge amounts of apparel waste, and textile production creates more emissions on an annual basis than maritime shipping and international air travel combined. Finding a way to make that technology more circular could have dramatic impacts.

We also just started a project with The North Face to replace polyester in outdoor apparel gear with a bio-based and biocompatible alternative. Most microplastics in fresh and marine water are polyester microfibers shed from clothing. If we can replace those materials with biocompatible fibers, then we could maybe reduce the long-term pollution caused by microfibers.

Knauer, who identifies with the fictional government powerhouse Leslie Knope from the TV show "Parks and Recreation," can often be found hiking, surfing, and running in the natural world she is working to protect. Photos from Katrina Knauer

This whole recycling thing sounds like a very complex puzzle.

It definitely is. It’s based on consumer access to and participation in recycling programs. Not everyone gets recyclables picked up at home. And if they do, they have to know what’s picked up and what isn’t. That will continue to be the most impactful part of recycling: the way consumers perceive and participate in it. I don’t know how to change that.

Any advice for folks who might want to follow in your footsteps?

Stop being worried that you’re the dumbest person in the room. That’s how many young researchers feel, and it keeps you from accomplishing so much. I wish I could go back to when I first started graduate school and say to myself, “You’re so awesome. Stop wasting so much time being worried about what people think of you.”

And remember how important your life outside of work is. Even when you love your job and you love science, the “life” part of work-life balance should be the most important.

We should enjoy this world while we save it, right?

Exactly.

Last Updated May 28, 2025