Q&A With Ana Aday: Why a Plucky Engineer Chose Cement Over Rodeo (But Credits Horses for Her Ability To Face a Crowd)

Ana Aday does not give up.

As a teenager, she had to leave high school early to take care of her family. She got a job in a big box store but was too curious to give up learning altogether. So, she earned her GED diploma and took calculus classes at her local community college—in part, so she could calculate complex sales prices for customers without grabbing a calculator.

Aday parlayed those credits into a bachelor’s degree from Southern Oregon University. At first, she wanted to be a nurse—to give back and help people—but math and physics soon stole her seemingly endless curiosity.

“My whole story is baby steps,” Aday said.

She took most of those baby steps alone. “I didn’t have many role models or even Google,” said Aday, who was also a low-income, first-generation student. Graduating with her undergraduate degree felt like not just a win but the win.

But that was just her start.

Today, Aday has master’s and doctoral degrees in materials science and engineering and works as a materials science researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Although she shifted from nursing to physics and finally to engineering, she did get her original wish: She may not be repairing human bodies, but she is fixing planetary bodies (namely, our Earth’s). To do that, she is starting with the stuff most of us walk on every day: cement and concrete.

“Concrete accounts for 8% of total global carbon dioxide emissions,” Aday said. “We can change things.”

Aday, who poured the first carbon-negative slab of concrete at NREL in July 2024, knows that even if she helps develop a more sustainable type of concrete, industry must still adopt it. She has to prove the new version is safe, durable, affordable, and can mimic the properties of today’s go-to materials. That is not easy, but Aday has high expectations.

“Specifically in concrete, I want to see us get to carbon negativity by 2050,” Aday said. “I don’t want us to get to 75% carbon negative. That’s not 100%.”

In this latest Manufacturing Masterminds Q&A, Aday shares why Bill Nye inspired her to become a scientist, how 3D manufacturing and artificial intelligence (AI) could help the cement and concrete industries decarbonize, and why handling a crowd of 1,000 people is the same as handling a 1,000-pound animal. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You had to overcome a lot of obstacles to get where you are today. How did you keep motivating yourself to push forward?

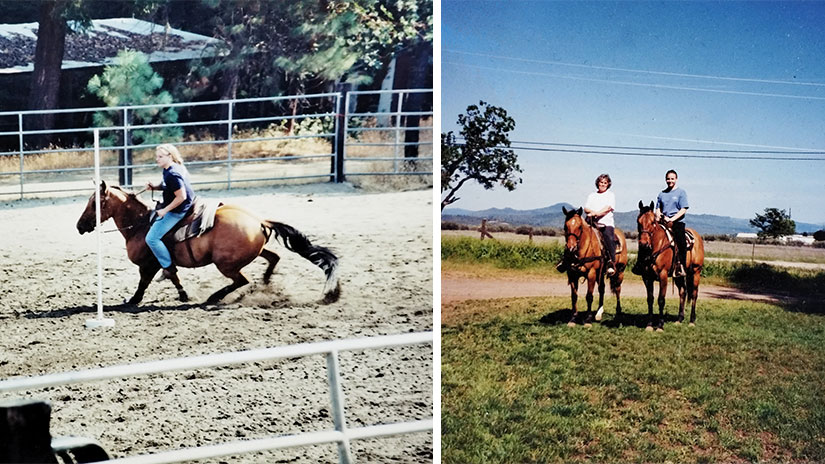

Everybody faces their own challenges. But my dad was a really good role model. He taught me hard work and perseverance. He never gave up. And I grew up on a farm with horses, so I knew about responsibility and overcoming fears. If I’m handling a 1,000-pound animal that could crush me or giving a talk to a crowd of 500 people, they’re the same. I get the same butterflies. But I learned how to overcome those fears and win over the crowd or horse.

What were some of the toughest obstacles you faced?

Being a low-income, first-generation college student was probably the biggest hurdle. It’s not like on TV. And being a woman in engineering—let alone construction engineering—you face so many different challenges. I just had to brush it off.

Would your young self be surprised to see where you ended up today?

Oh, yeah. I was a really good academic in high school. So, even though I needed to leave high school before getting my diploma, I wasn’t done with school. But I honestly thought I would still be on the farm raising and showing horses and doing rodeo. I had no intention of going to college. I thought I’d just get a good job so I could afford my horses. Then eventually, I’d make rodeo my full-time job. But I was always interested in science. I was obsessed with "Bill Nye the Science Guy" and "NOVA." I thought I would be proud to say I’m a scientist.

How did you end up going back to school and pursuing a career as a scientist?

At community college, I got enough credits to transfer to a four-year university. I needed SAT scores, which I didn’t have, so I totally scooted in the back door. Then, when I graduated, I was so tired of science—I majored in physics and minored in materials science—that I took a job working for a U.S. Department of Education program, tutoring people to help them get through their classes and working as an office coordinator. I wanted to give back.

Aday grew up riding horses on her family’s farm, but she also frequently raided the kitchen to replicate experiments she saw on "Bill Nye the Science Guy." Even though she thought she would end up in rodeo (or working as a nurse, so she could take care of people), she eventually got sucked back into science. Photos from Ana Aday

At that point, you didn’t want to do science anymore?

Correct. But my boss was an educator, and she told me, “You have a talent. You need to think about graduate school.” My parents have high school educations. I thought I did good with the bachelor’s degree. But when I started looking at jobs in my local area, I saw I would need at least a master's degree if I didn’t want to limit my opportunities.

So, I applied to two master’s programs in materials science. I could barely afford the test you need to take for graduate programs and could only afford two application fees, so I only applied to two schools. No one told me you could get your doctoral degree paid for. Plus, I was scared. I didn’t know if I could handle a doctorate. But I got into the University of Colorado Boulder’s master’s in materials science program, which is how I ended up in Colorado.

How did you end up in a doctoral program focusing on cement and concrete?

My advisor, a civil engineer, asked if I had ever considered concrete. I thought we had concrete figured out. We walk on it every day. Turns out there’s a lot of science there. I was doing good work in the lab, so I ended up pursuing a doctorate with him, working on biobased technologies for concrete applications, meaning technologies made from materials like plants or agricultural waste instead of petroleum.

How did you end up at NREL?

My advisor told me there was probably an internship opportunity at NREL. So, he connected me with the buildings group, and not even two weeks after I graduated, I started as an intern. I worked on thermal energy storage initially, and I loved that. Then, a funding opportunity came out for low-carbon, carbon-negative concrete, and my NREL colleagues were like, “We know just the person.”

I love it here. I love the people. I love the work. I always wanted to bridge the gap between what I do and what it means to people. That’s what I do at NREL, bridge the gap between research and industry. I’m here to get cool things out into the world.

What kinds of cool things are you working on?

I’m developing carbon-negative concrete and alternative materials that can supplement cement. The core focus is the material’s structure and performance. Developing carbon-negative materials is one thing, but if they don't perform well in real-world applications, then their value is negligible. But then, I also have to put on my business hat. When I’m talking to industry partners, I have to explain how the material is scalable and feasible. Concrete is pretty well known. It's strong. It's durable. Industry doesn’t want to move forward with a brand-new material if it’s never been demonstrated. That’s a risk to human life.

How does manufacturing fit into your work, and what do you think is the biggest challenge manufacturing faces today?

The U.S. industrial sector is hard to decarbonize because it’s so diverse. Manufacturing cement inherently releases carbon dioxide. That’s a material issue that many are working to solve. There are also transportation issues, like the trucks and diesel fuel needed to transport the materials. That’s why manufacturing fits well into my work. I can assess a product’s life-cycle emissions from cradle to grave.

For example, for concrete, you always overdesign and overmix, so there’s always some waste. I’m looking at additive manufacturing processes, robotics, and artificial intelligence, so we can know exactly how much material you need to print a house or a wall and limit waste.

Speaking of waste, don’t cement and concrete often use up waste from other industries?

Yes, we use industrial byproducts to offset the amount of cement that we use, but those processes are also being decarbonized. We use fly ash from coal-fired power plants and blast furnace slag as an alternative supplementary material for concrete. But those byproducts are going away and the quality is changing, so we need new options. For example, the Romans used volcanic ash in their concrete. So, we’re looking at ways to adapt to decarbonization across many coupled industries, like steel and concrete.

In an ideal world, what would you most hope to accomplish?

We all have to live on this world, and we need to take care of it the best we can. Today, we’re paying for all the changes we made during the industrial revolution. I want to spend my career getting us to 100% carbon-negative concrete by 2050. It’s OK to fail, but fail fast. And we need everybody’s input. We’re not here to sit around and wait. Let’s go.

What advice would you give to other first-generation students?

Find yourself a mentor and be proactive about it. They don’t come to you. And just ask questions. I didn't just pick a Ph.D. lab randomly. I interviewed about 10 different professors until I found what I was looking for. And don’t silo yourself; be open to all possibilities. That’s the fun part. You never know what you're going to find.

Interested in building a clean energy future? Read other Q&As from NREL researchers in advanced manufacturing, and browse open positions to see what it is like to work at NREL.

And check out our Work With Us page to learn how you can collaborate with our experts and help forge a clean energy future.

Last Updated May 28, 2025