Tim Silverman Likes Breaking Things—and That Is Good for Photovoltaic Reliability

Materials Scientist Is One of NREL’s 2024 Distinguished Members of Research Staff

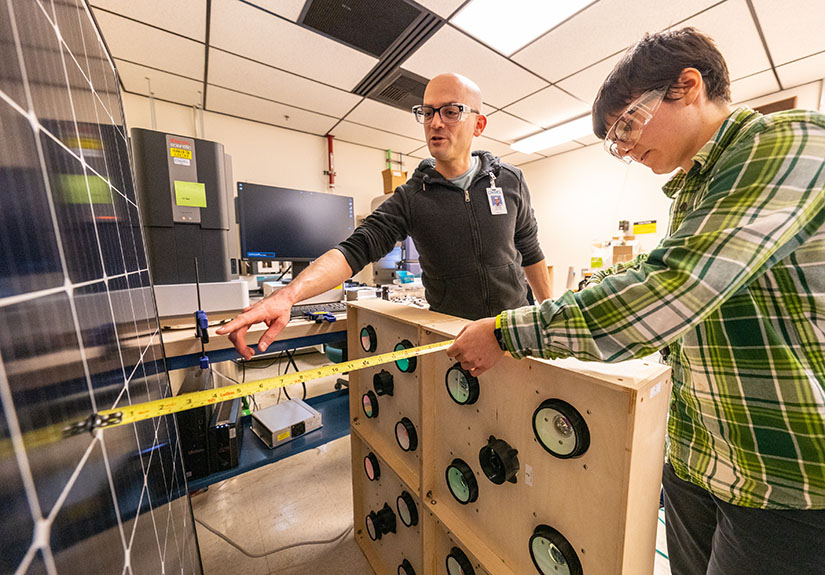

Tim Silverman explains some NREL projects for participants in the 12th Hands-On PV Experience in 2023. Photo by Werner Slocum, NREL

Tim Silverman was good at breaking and then unbreaking things as a boy growing up in Houston, Texas. “I have at least two types of breaking I did as a kid,” the Materials Science senior scientist said.

“I took lot of already broken stuff apart: dishwashers, washing machines, radios, and TVs to see what was in there,” he said. Then, he would try to get it back together again. Such activity had a purpose, he added, and was not merely destroying gizmos in a rage. Instead, he was deeply curious.

The other action Silverman enjoyed was to repeatedly try out devices by putting them through endless repetitions. “I would push the button that locked the car door on my dad’s Mazda GLC a million times. He’d ask: ‘Are you stress testing that?’ It must be satisfying to him that I do actually do stress testing.”

This behavior is one of the through lines in the 41-year-old’s life. He has essentially been testing devices since joining NREL in 2011—talents he showcased in two NREL YouTube videos. One demonstrates a means he invented as a way of doing artificial weathering of photovoltaic (PV) cells faster; the other shows how to detect flaws in solar panels.

Ending up a scientist—even one with a penchant for destruction—was probably in the cards for Silverman. Because his father was a brain scientist, Silverman was exposed to the laboratory setting as a youngster.

That environment also enabled him to become a bit of a computer whiz in the 1980s and 1990s. At the age of 5, Silverman had what he called the “privilege” of testing out obsolete machines from the university where both his parents worked. He began with an Intel 8088 microprocessor.

Along the way, he fiddled with the machines so they could run faster. Silverman quickly became at ease with this new reality, saying, “As soon as I could, I stopped handwriting homework assignments. I was the kid who typed everything. It annoyed my peers.”

Even though he may have been a bit different from most of his other schoolmates, and for a time even carried a briefcase, which was not the norm, Silverman reached out to them in other ways. On the humid school buses in Houston, he shared some of his inventions with classmates.

“I made lots of weird portable fan contraptions. That was before you could buy an electric fan in the dollar store,” he said. Although often the inventions quickly broke, the gestures were nonetheless well received.

Despite such early encounters with climate extremes, renewable energy technologies were not on his radar at first. While pursuing a mechanical engineering degree at Arizona State University, he spent two summers working in a defense industry factory in Tucson. The job paid well.

But a conversation with his uncle planted a seed in his mind. Silverman remembered that his uncle told him that the real action for an engineer would be in saving the planet.

Three or four years later, Silverman took the advice to heart and found a way—with his Ph.D. advisor’s permission—to experiment with fuel cells.

Silverman's Big Break at NREL

Even with this first step toward renewable energy in the form of fuel cells, Silverman did not exactly seek out NREL. Instead, he said he merely followed his wife Anne to Colorado when she took a job as a mechanical engineering professor at the Colorado School of Mines.

One day Silverman saw an NREL job posting that sought someone who could build a computer model to simulate the behavior of an unusual material—something he had done before in his Ph.D. He applied, and after a phone interview, showed up a week later for an interview with the model running on his laptop. He was hired soon after, in February 2011.

His first mentors at NREL were researchers Nick Bosco and Sarah Kurtz. Kurtz was a trailblazer in photovoltaic research (profiled in NREL’s Clean Energy Innovators book) who later pivoted in her career to reliability. She believed reliability was critical for the acceptance of solar energy.

“If Sarah said something was important, I’d work on it. Things progressed according to what the industry needed,” Silverman recalled. For instance, there was an early case of a solder bond cracking in a PV cell. Tim jumped in to analyze the problem and then to refine a test for it.

As technologies changed—and they did often—he would begin the process over again, whether the issues were plaguing concentrating photovoltaics or thin-film technology. First he would learn how to detect the problem and try to understand it by making things break in the same way. Then he would make the problem happen in the lab or in the computer so future product designers could avoid it.

As he was getting established, Silverman shared an office with Mike Deceglie, and together the prolific duo combined talents on many research papers over the course of about eight years.

Researcher Nicole Luna and senior scientist Tim Silverman make adjustments to the PLatypus, a device that allows the user to see cracks in solar modules, to help determine if the panels are damaged and might need to be replaced, at NREL’s Outdoor Testing Facility in 2023. Photo by Werner Slocum, NREL

Quickly, Silverman’s reputation grew. In 2019, he and Mike Wagner became the first researchers at NREL to receive the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. The PECASE awards, the government's highest award for early-career researchers, were established in 1996.

Silverman’s award in the field of reliability was a mouthful. The award was for “significant contributions to the field of solar energy through application of innovative new methods to the characterization of commercial photovoltaic or PV module designs and for discovering a critical defect in commercial modules that had otherwise gone unnoticed for years.”

In accepting the honor, Silverman cited not only Kurtz and Deceglie but also Chris Deline and John Wohlgemuth as key supporters in his research. Around 2016, Ingrid Repins took over from Kurtz and further supported Silverman.

Deline remains a huge fan. “I have been Tim Silverman’s manager since 2021 but have worked side by side with him in the PV performance and reliability group since 2011, and I am continually astounded by his creativity, brilliance, and impactful research.”

Not surprisingly, other awards have come Silverman’s way too. This year, he was named one of NREL’s Distinguished Members of Research Staff (DMRS).

Always up for new challenges, Silverman retains his passion for research. “PV changes, and the products commercialized change every six months or so. There are new problems, and we have to invent new stuff to catch them,” he said.

While he still generally does what is covered in the aforementioned YouTube videos, he has a new focus now. “Today my top concern is broken glass. I’m surrounded by 100 PV modules we’ve recovered from power plants where the glass has broken," he said. "This has been happening more often. There are a lot of possible reasons, and we don’t know which is the real one. Glass is important to PV. We are learning why it breaks so we can develop tests to catch this problem. We help manufacturers improve future products.”

He is not just a whirlwind in the lab but takes time to explain his results and their impacts. For example, he is a key author on their Solar Futures Study, which lays out the pathways to reach the nation’s climate goals with solar technology as a major contributor.

“Ever since I left the factory, I have been heavily mission oriented. Now the mission is to slow down climate change,” he said. “That’s where we should be putting our resources.”

Silverman does not spend all his time wreaking havoc. To relax, he will play the video game Tetris, which has been around since 1985 in various forms. Silverman recently finished among the top players in a monthly Denver, Colorado, tournament. “I took a bronze,” he joked.

One thing he will not break from is NREL. And from the looks of it, there are not many people as good as Silverman at figuring out how to break things—so they can be rebuilt to become better tools to fight climate change.